The Australian ancillary copyright called “News Media Bargaining Code” is supposed to oblige Google, Facebook and Co. to share advertising revenues with publishers. Facebook does not agree and is now blocking all news in and from Australia. A scenario that also threatens Germany.

Facebook blocks all news in Australia

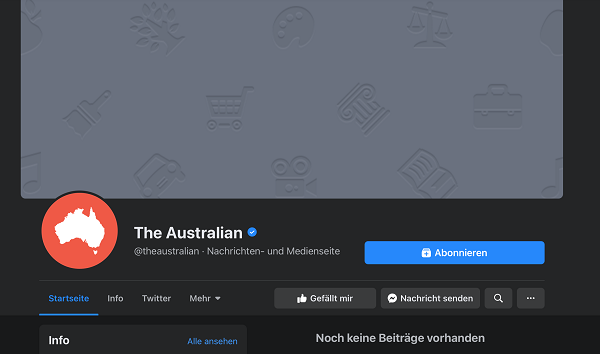

The dispute over the ancillary copyright (LSR) in Australia has reached its next stage. Facebook is blocking all journalistic news in Australia. Campell Brown, Head of News Partnerships at Facebook, confirms.

It was our goal to find a solution that strengthened our collaboration with publishers. But the legislation failed to establish the fundamental relationship between us [Facebook; ed.] and news organizations.

William Easton, Facebook’s managing director responsible for business in Australia and New Zealand, explains the specific consequences of the decision in a blog post.

For example, due to the ancillary copyright in Australia, neither users nor publishers can now share news and articles from Australian and international media on Facebook. Publishers now only have the option to view analytics on their pages.

Facebook users in other countries can no longer view or post Australian news. However, there still seems to be differences in this at the moment. A spontaneous test in the editorial office of BASIC thinking showed that everything is partially blocked.

However, other members of our editorial team can see Australian news sites as well as share links and articles from Australian media.

Performance protection law in Australia obliges Google, Facebook and Co. to make payment

But why did this step have to be taken in the first place? A new ancillary copyright law (LSR) has been in force in Australia for several weeks.

It requires Internet companies such as Facebook and Google to share their advertising revenues with publishers. Ultimately, the platforms are to pay a license fee for the distribution of news content.

This is precisely the point where Facebook is now making its case. According to the social network, publishers intentionally share their content on Facebook because they can sign up more subscriptions, increase their target audience and boost their ad sales.

In contrast, it says, “Google search is inextricably linked to news and publishers who don’t volunteer their content.” That Facebook manager William Easton holds this opinion is clear. After all, this is how he pushes the proverbial buck to the competition.

However, the discussion about ancillary copyright in Germany, for example, shows very clearly that small publishers in particular do share their content with Google voluntarily because they benefit from the enormous reach.

Google pays fees to publishers in Australia

However, compared to Facebook in Australia, Google is certainly willing to negotiate.

Australian Finance Minister Josh Frydenberg confirmed to the media that there are already goal-oriented talks or agreements between Google and Australian media houses such as Seven West Media, Nine Entertainment and the public broadcaster ABC.

The so-called News Media Bargaining Code in the new ancillary copyright would therefore create movement in the market. Seven West Media could receive between 25 and 40 million euros from Google.

Are publishers in Germany also threatened with shutdown?

At the moment, the situation in Australia sounds like a horror scenario for German publishers. However, such reactions – especially from Facebook – are closer than one might expect in this country as well.

The reason for this is the new regulation of copyright law in Europe. In addition to the heatedly discussed upload filters, this law also provides for a performance protection right.

Ironically, the drivers behind the reform are, of all things, more than 25 German and European newspaper publishers who see the financing of their content at risk and are therefore insisting on payments from Google, Facebook and Co.

At the head of the reform drivers is Axel Springer, a major publisher that is apparently wilfully dragging small and medium-sized publishers down with it, as the example from Australia now shows. The social networks and platforms are not all buckling, but are simply blocking out content.

This hits small publishers particularly hard because, unlike Springer media such as Bild or Welt, they do not have reach in the millions. For the small ones, Facebook and Google represent relevant traffic channels.

If the dispute between legislation in Germany and Europe on the one hand and digital corporations like Facebook and Google on the other also escalates, it could well be that we will no longer be able to share news in Germany in the not too distant future.